Tips on Diagnosis and Management For the Non-bariatric Surgeon

By Monica J. Smith

Many general surgeons have only six weeks or so of training in bariatric surgery during residency, but they are likely to encounter post-bariatric surgery patients who will need their help.

At the American College of Surgeons 2020 virtual Clinical Congress, surgeons discussed their approaches for treating these patients, who should see them, and when surgical intervention is urgent.

‘Everyday’ Operations in Complicated Patients

Peter E. Fischer, MD, MS, an associate professor of surgery at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, in Memphis, is not a bariatric surgeon, and his hospital, Regional One Health, doesn’t have a bariatric program.

“But these patients still show up in our emergency department [ED], as I’m sure they show up in yours, and there are ways to walk through general surgery issues.”

Some of the reasons post-bariatric patients arrive in the ED have nothing to do with their bariatric surgery. “Just because they had bariatric surgery doesn’t mean they don’t have appendicitis,” Dr. Fischer said.

Other conditions, such as gallstone disease, may be more prevalent in patients who have undergone bariatric surgery but are still fairly common in the general population and familiar territory for general surgeons.

But people who have undergone bariatric surgery can present unique challenges; it’s wise to get a comprehensive history: What type of bariatric procedure did they have and when, how many operations since then, and who did their procedure? “These can be complicated consults and complicated patients, and continuity of care is important,” Dr. Fischer said.

If the bariatric procedure was conducted recently, within the last six months, or if the patient is experiencing an early complication specific to bariatric surgery, he advises trying to send the patient to a bariatric specialist: “ideally the surgeon who performed their procedure,” he said.

Otherwise, general surgeons are equipped to handle the needs of most post–bariatric procedure patients. As Raul Rosenthal, MD, said, “The acute abdomen belongs to the surgeon on call.”

Early Complications

Early complications are major complications, and should be treated by a bariatric surgeon. The two early complications that occur after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass are bleeding and leaks; they are distinguished from each other by heart rate.

“When patients develop a leak, they will have sustained tachycardia, above 120 [beats per minute] regardless of pain medication or antibiotics. But when the patient has a bleed, their heart rate doesn’t just go up; it also becomes very cyclic, from 80 to 120 to 90 to 110,” said Dr. Rosenthal, the chief of minimally invasive and bariatric surgery at Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Fla.

Bleeding occurs in about 4% of patients. Surgeons first need to determine whether the bleeding is intraluminal or intraabdominal, and then identify the bleeding site, whether from anastomosis, staple lines, mesenteric defects or trocar sites. “Patients should be transferred to a monitored setting; surgical decision making depends on clinical signs and symptoms,” Dr. Rosenthal said.

Leaks occur after about 1.7% of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures; the treatment is drains, drains and more drains.

“If the patient is hemodynamically unstable and has no drains, they get a drain and a gastrostomy. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable with a drain, we need to add more drains and clear the area of infection. In the hemodynamically stable patient with a drain, all you need is total parenteral nutrition, antibiotics and observation,” Dr. Rosenthal said.

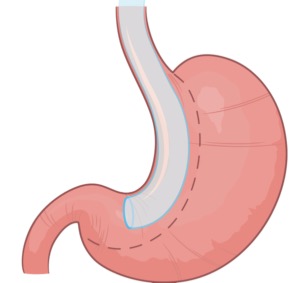

The most common early complications after sleeve gastrectomy are bleeding and staple-line disruption, the treatment of which depends on localization. “Most leaks are in the proximal aspect of the staple line and depend on bougie size. The smaller the bougie, the higher the chance the patient will have a staple-line disruption, and 90% of those are located near the gastroesophageal junction,” Dr. Rosenthal said.

While acute staple-line disruptions in unstable patients require re-laparoscopy and drainage, chronic patients will require proximal gastrectomy. “Stents and glues are acceptable in the first one to 12 weeks; after that, the patient will most likely need a surgical intervention.”

Late Complications: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass And Sleeve Gastrectomy

The most common late complications after gastric bypass are cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis, which are more frequent in bariatric patients than in the general population since the discontinuation of routine prophylactic cholecystectomy, said Kimberly M. Davis, MD, MBA, a professor of surgery at Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven, Conn.

Cholelithiasis can be treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but choledocholithiasis is a bit more complicated due to the altered anatomy of gastric bypass patients, and it requires collaboration with a gastroenterologist.

“Patients with common duct stones after gastric bypass can be managed with either a laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, or with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography performed through the gastric remnant in the operating room,” Dr. Davis said.

About 5% of gastric bypass patients experience marginal ulceration. Unperforated ulcerations can be managed with resumption of proton pump inhibitors. Perforated ulceration calls for IV antibiotics with or without percutaneous drainage.

“But when a perforation requires exploration, the best management is wide drainage, oversewing of the perforation and an omental patch,” Dr. Davis said.

The most concerning complication after gastric bypass is bowel obstruction, which often stems from internal hernias that can lead to bowel ischemia and strangulation. “The internal hernia can be deadly if missed,” Dr. Fischer said.

Mesenteric swirl on CT imaging is indicative of bowel obstruction, but imaging findings can be misleading, Dr. Davis said.

“CT scans read as normal in 30% of cases. So, you need a high index of suspicion in a patient who presents with midepigastric and periumbilical abdominal pain that is sudden in onset and may radiate to the back. The best way to manage these is with diagnostic laparoscopy for confirmation.”

Laparoscopic reduction and repair of the defect is feasible, but the anatomy can be challenging, especially for surgeons who don’t see many post-bariatric patients, Dr. Fischer said. “Starting at the terminal ileum, where the anatomy is exactly the same, and working your way backward is a nice way to get everything reduced. Though laparoscopic repair is preferable, don’t hesitate opening.”

After sleeve gastrectomy, about 4% of patients will experience a stenosis, which is often a late consequence of an undiagnosed or subclinical leak that results in a dilated proximal pouch. “This can be relieved through lysis of adhesions,” Dr. Davis said.

Short-segment stenosis can also be managed via balloon dilation. Longer segments may require bariatric surgery revision, “though there are increasing reports of balloon dilation and placement of 15-cm endoluminal stents, which can be removed after several months,” Dr. Davis said.

Late Complications: Gastric Banding

Gastric banding is now the least popular type of bariatric surgery, but there are still an estimated 700,000 to 1.2 million bands out there, and about half of them will require surgical intervention at some point. The two main late complications are band slippage and band erosion, both of which require band removal.

Band slippage occurs when a portion of the stomach slips up through the band. This is diagnosed on kidney, ureter and bladder x-ray when the band appears as an O shape rather than showing the proper angulation.

“There’s a good chance we’ll need to be concerned about the vascular supply to the portion of the stomach that’s above the band,” said Christopher DuCoin, MD, MPH, an associate professor of surgery and the chief of the Division of Gastrointestinal Surgery at the University of South Florida, in Tampa.

If the patient presents with symptoms that could be related to the band, start by deflating the band, using a Huber needle to remove fluid from the port. “Usually this can be done by simply palpating the port, but you might need to use fluoroscopy. The patient should experience improved symptoms shortly thereafter,” Dr. DuCoin said.

To remove the band, use any device, such as an ultrasonic scalpel, to release fibrotic tissue around the band, he continued. “Once it is mobile, just cut through it. I recommend cutting the side opposite the buckle.”

Having released the band, Dr. DuCoin removes it through a 15-mm trocar, documents that all of the band is out, deflates the abdomen and removes the subcutaneous port.

Band erosion looks like an emergency, but it isn’t, Dr. Davis said. “Band erosion occurs over time, and any perforation is sealed by the surrounding inflammation as the perforation occurs.”

Patients often complain of upper abdominal or back pain and may have melana. “But more commonly they will have an infection of the port,” Dr. Davis said.

There are a couple of options for removal, Dr. DuCoin said. “You can do a completely endoscopic removal of the band, ligating it and using a snare to remove it; or you can do a laparoscopic resection.”

The surgical technique Dr. Davis uses is to mobilize the left lobe of the liver, then identify and follow the path of the band to the band and buckle, which are usually located on the lesser curve of the stomach.

“Once the band has been mobilized,” Dr. Davis said, “it can be cut and the entire structure removed through a 15-mm port.”